Why is this project relevant?

Photo by Fundacion Protejamos Patagonia

The transformation of natural habitats into cropland and ranch lands is one of the major threats to biodiversity globally. The colonization by Europeans of the Argentine Patagonia caused strong modifications of the natural steppes and grasslands of this vast territory. Settlers introduced sheep towards the end of the 18th century, and in 50 years an estimated 50 million of the animals grazed the natural vegetation causing habitat degradation and local processes of desertification. In addition to sheep, several wild mammals were also introduced.

Habitat loss, modification and changes in mammal community composition interacted with persecution to create an environment that was no longer suitable to several wild species.

We know that pumas (Puma concolor) and guanacos (Lama guanicoe) were eliminated from most of the Patagonian lowlands and that culpeo fox (Lycalopex culpaeus) populations were greatly reduced. These species have recolonized most of Patagonia in the last decades thanks to the reduction in sheep stock. This was caused by a sharp decrease in the price of wool and in productivity, because habitat degradation caused by the grazing sheep provoked desertification. However, we have absolutely no idea of the effects these processes had on the population of small wild cats. We do not know their population size or the threats to their conservation.

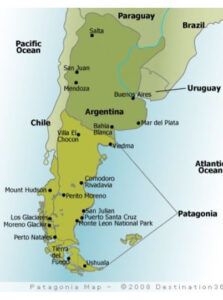

The distribution range of two species of small wild felids extends to the southern latitudes of the Patagonian lowlands: the Geoffroy’s cat (Leopardus geoffroyi) and Pampas cat (Leopardus colocolo pajeros). With a size of 673,000 sq km, the Patagonian steppe ecoregion in Argentina represents a large portion of the distribution range of both the Pampas cat and Geoffroy’s cat.

The Pampas cat has been very poorly studied, but it is considered rare throughout most of its distribution range and close to extinction in the Pampas grasslands of Argentina. Because of this rarity and the loss of natural habitats that is affecting many of the regions where it occurs, the Pampas cat is listed as Near Threatened globally and Vulnerable in Argentina. However, this categorization is based on the assumption that the Pampas cat is a single species, while the most recent and comprehensive reviews of its taxonomy strongly suggest that it should be divided into 5 species. If we accept this new taxonomy, the Pampas cat populations inhabiting the Patagonia would belong to species L. pajeros and its conservation status would require urgent assessments, also because this species is currently receiving little conservation attention in Argentina (Lucherini et al. 2018).

In comparison to the Pampas cat, the Geoffroy’s cat has been more studied and is considered relatively common across most of its distribution range, which led to its categorization as Least Concern both globally (Pereira et al. 2015) and nationally. Nevertheless, the scant evidence we have indicates that the Geoffroy’s cat may be rare and even absent from portions of the Patagonian steppe.

In summary, the information on the presence of these wild cats in the steppe habitats that occupy the lowlands of Patagonia is still extremely scarce and nothing is known about their population abundances. This lack of knowledge would not necessarily be a reason for concern if it was not for the understanding that sheep ranching has caused extensive modification to natural habitats and to the native wildlife of Patagonia. There is also clear evidence that there are intense and deeply-rooted conflicts between carnivores and ranchers in this region and that ranchers frequently kill small cats because they perceive them as predators of lambs and chicken.

The Patagonia Cats Project (PCP) aims to fill this gap and improve our understanding of the natural history and conservation threats of the Pampas and Geoffroy’s cat populations in the Patagonian steppe. However, we also plan to start actions to reduce threats as soon as they are identified by working locally with different social actors.

How can we do it?

The Patagonian steppe is a very large territory; thus, I am actively promoting collaboration with other researchers, governmental agents, and conservation practitioners. I have already created a network that will share information on cat presence but also awareness material, to amplify the reach of my project and facilitate achieving its goals.

The Patagonian steppe is a very large territory; thus, I am actively promoting collaboration with other researchers, governmental agents, and conservation practitioners. I have already created a network that will share information on cat presence but also awareness material, to amplify the reach of my project and facilitate achieving its goals.

Information on cat distribution and abundance will be obtained by camera trap surveys. Cameras will be displayed in a set of sites representative of the diversity of habitats of this region, both in protected areas and private ranches. To understand conservation threats, we will interview local people, especially ranchers. In person interviews are very effective at learning the human dimension of conservation problems, such as the conflicts between carnivores and local people related to predation on livestock and to collect information for species that are rare or difficult to detect.

As soon as we have a better idea of those threats, we will design and implement tools to address them in specific forms. Meanwhile, we will carry out awareness activities with adults on the ecological role of these species (with emphasis on the control of rodent populations), and provide information on how to easily build predator-proof chicken coops. Simultaneously, we will conduct environmental education activities in rural schools to create pride among children of having these beautiful species in their country.

By Mauro Lucherini

December 2022