The Black-footed Cat Working Group’s (BFCWG) aim is to conserve the rare Black-footed Cats (abbreviated as BFC hereafter) by promoting awareness and conducting research on their biology. So far the group has concentrated on two study areas in central South Africa. It became apparent that to become a truly international project, research and conservation on the species needed to extend to neighbouring countries and other habitats. For this reason the three authors of this report undertook a survey in January 2019 in southern Namibia.

There have never been any BFC studies in Namibia. Once a promising conservation area, farm and region are found, the aim is to start an intensive study. Location records reported by farmers over the last 5 years have been invaluable in establishing distribution in Namibia and potential areas for future studies.

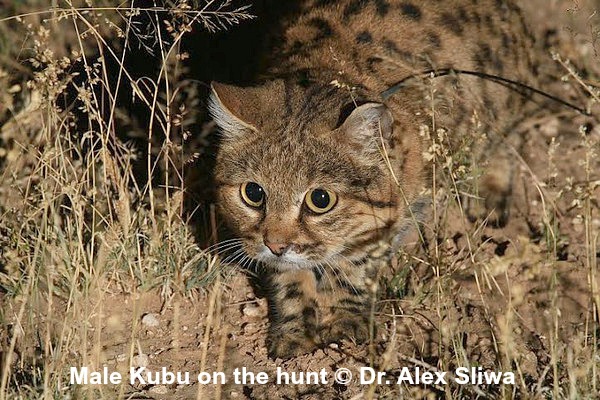

Valuable BFC census data in Namibia was collected on this first scouting trip. With a total of four different individual BFCs sighted, one in Gondwana Canyon Park and three over only two nights on the Grünau S.W. farm, the latter was identified as the most promising site for establishing an intensive study area. Altogether the sighting frequency of four cats over eight nights surveyed provides a 50% chance of a sighting. When taking Grünau S.W. by itself a sighting of 1 and 2 cats each per night, this reached a 150% chance of BFC sighting per night. This sighting frequency is comparable or greater than those attained over the past 10 years in the two long-term study areas of South Africa.

Interestingly the sighting of a juvenile in the Canyon Park is proof of a breeding population in this protected area. Being only 44km away from sightings on the Grünau S.W. farm, it shows that these are well within reach of a dispersing young adult BFC from the Canyon or even an adult male with an extensive home range.

It will be interesting to study individuals of both populations and see where they link or if it’s a continuous population. Compared to the two South African study sites with averages of 450 and 300 mm precipitation annually, Grünau S.W. receives only 125 mm annually, so it is expected that BFC home ranges and ranging behaviour will be more extensive than previously published.

It will also be interesting to capture and radio-collar some of the numerous African wildcats (Felis lybica cafra) in the area to see how the two small cat species interact, compete or separate in their ecology.

Researchers will need permits for capturing and collaring BFCs in Southern Namibia, and funding for telemetry equipment, and tuition for a student who will do the monitoring. They will also need to hire a Namibian veterinarian for the anaesthesia capture operation. Southern Namibia is much drier and a true desert, so conditions are different for the cats compared to South Africa.

The Black-footed Cat will be included in the Red List Assessment of Carnivores in Namibia, and the species listed as Protected or Specially Projected under the new Protected Areas and Wildlife Management Act. This will enable better conservation action and more focused research.

Report on Black-footed cats (Felis nigripes) survey in southern Namibia. Alexander Sliwa, Martina Küsters & Morgan Hauptfleisch

You can help these tiny cats! 100% of donations will go directly to the Black-footed Cat project.

We’ve updated our Sand cat fact sheet with new information on their distribution and conservation threats.

We’ve updated our Sand cat fact sheet with new information on their distribution and conservation threats.